Lean 3 (archive)

| Logic | Intro | Elim |

|---|---|---|

| \(\rightarrow\) | intro intros |

apply have h_3 := h_1 h_2 |

| \(\forall\) | intro intros |

apply specialize have h_2 := h_1 t |

| \(\exists\) | use |

cases |

| \(\lnot\) | intro intros |

apply contradiction |

| \(\land\) | split |

cases h.1 h.2 h.left h.right |

| \(\leftrightarrow\) | split |

cases h.1 h.2 h.mp h.mpr rw |

| \(\lor\) | left right |

cases |

| \(\bot\) | N/A | contradiction ex_falso |

| \(\top\) | trivial |

N/A |

Classical logic open_locale classical use by_contradiction tactic

Most of the time, implication and universal quantifier are treated the same.

1 rw

- given

h: a*b=b*a

rw hmeans attempt to transform consequent usinga*b->b*a⊢a*b+cturns into⊢b*a+c

rw <- hmeansb*a->a*b⊢b*a+cturns into⊢a*b+c

1.1 Example

expected type:

abcd: ℝ

h₁: a ≤ b

h₂: c ≤ d

⊢ ∀ {α : Type u_1} {a b c d : α} [_inst_1 : preorder α]

[_inst_2 : has_add α]

[_inst_3 : covariant_class α α (function.swap has_add.add) has_le.le]

[_inst_4 : covariant_class α α has_add.add has_le.le]

, a ≤ b → c ≤ d → a + c ≤ b + dType

For any type α that has a pre order.

2 Types

if p : Prop then

x:p is a proof of proposition p : Prop.

if y:p is also a proof then proof irrelevance means x:p and y:p are indistinguishable.

- Props, terms

- Given \(P:Prop\) , the term \(h:P\) is a proof of \(P\)

- Implication \(P \rightarrow Q : Prop\) is the function type

- Given \(h1: P \rightarrow Q\) , \(h2:P\) conclude \(h1\ h2: Q\)

- Quantifier and Dependent Function type

- Given \(P:X \rightarrow Prop\) represents \(\forall( x: X). P\ x: Prop\)

3 Numbers

Proofs of numbers typically use type coercion.

norm_num4 Inductive type

inductive mynat

| zero : mynat

| succ (n : mynat) : mynat5 Definitional Equality and Reduction

- Given

- \(A \overset{reduces}{\rightarrow} X\)

- \(B \overset{reduces}{\rightarrow} X\)

- Implies

- \(A \underset{def}{\equiv} B\)

| Conversion | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| alpha | renaming | \(\lambda x. P x \equiv \lambda y. P y\) |

| beta | computing | \((\lambda x. x + 2) 3 \equiv 3 + 2\) |

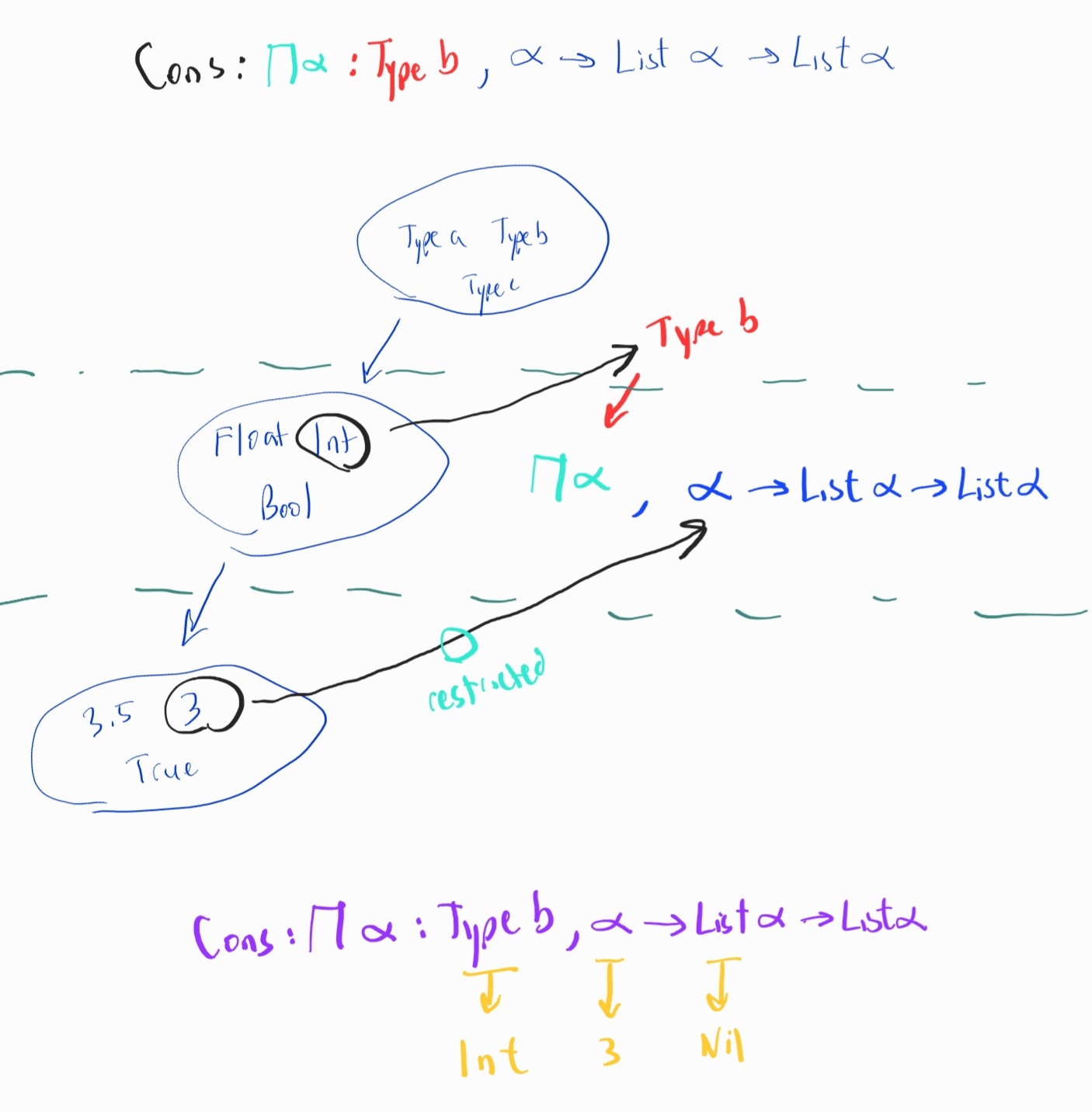

6 Dependent type

6.1 Inspiring the dependent type

cons 2 [3,4] : List Nat

cons : Nat -> List Nat -> List Nat

What if we wanted a polymorphic cons?

Give first argument as the Type

cons Nat 2 [3,4] : Type -> T -> List T -> List T

- Nat : Type

- 2 : T

- [3,4] : List T

Notice T = Nat

We need T in Type-Space to relate to Nat in Term-Space. How?

Abstract away the term Nat to a bound term variable Π T

Type -> T -> List T -> List T =>

Π T : Type -> T -> List T -> List T

namespace hidden

universe u

constant list : Type u → Type u

constant cons : Π α : Type u, α → list α → list α

constant nil : Π α : Type u, list α

constant head : Π α : Type u, list α → α

constant tail : Π α : Type u, list α → list α

constant append : Π α : Type u, list α → list α → list α

#check cons α a (nil α)

end hiddenObserve how we can use Dependent Product Type for polymorphism.

\[\prod_{x: \alpha} \beta = \prod_{x: \alpha} (x \rightarrow list\ x \rightarrow list\ x)\]

Pi-type or dependent product type behaves like lambda in the type space

β is an EXPRESSION that can be expanded.

β may or may not include bound variable x in it’s expression

cons :: Π x : α, β

What is the type of cons int?

We apply (Π x : α, β) to int in the type space.

cons int :: (Π x : α, β)(int)

(Π x : α, β)(int)- Beta-reduction:

β[int/x]

βexpanded isx -> list x -> list x

β[int/x]is(x -> list x -> list x)[int/x]

- replace x with int resulting in

(int -> list int -> list int)

cons int :: (Π x : α, β)(int) is

cons int :: int -> list int -> list int

Example of a list is cons int 3 (nil int)

Since cons and nil are dependent types, they must take an extra parameter [in this case] int

f :: Π x : α, β = f x :: β[x] where x :: α

6.1.1 function type is just a Pi-type

when

βexpanded expression does not include

bound variableΠ x : αthen

β[x]=β

example:

f :: Π x : α, β = f x :: β[x] = f x :: β = f :: α -> β

example β is bool, α is nat

Notice bool is an expression that does not include any bound variable x:nat

even :: Π x : α, βeven :: Π x : nat, booleven :: nat -> bool

6.2 Sigma Type

def f (α : Type) (β : α → Type) (a : α) (b : β a) : (a : α) × β a :=

⟨a, b⟩

def h1 (x : Nat) : Nat :=

(f Type (fun p => p) Nat x).2

-- (α : Type) is (Type : Type)

-- β is (fun p => p : Type -> Type)

-- (a : α) is (Nat : Type)

-- (b : β a) is (x : (fun p => p)(Nat)) which is (x : Nat)How to look at f? Extract the types

Type -> (α → Type) -> α -> β a -> ((a : α) × β a)

7 Notation

7.1 Curly vs Smooth Parenthesis

- Curly

{a: Type u}stands for notational shortcuts aka implicit arguments that do not need to be written - Smooth

(a: Type u)stands for explicit aka we need to write out the type as an argument

---- Curly vs Bracket

---- {a: Type u} vs (a: Type u)

---- implicit argument vs explicit

--They mean the same but implicit argument allows us to omit arguments for shorter declarations.

--implicit argument means that {a: Type u} will get autofilled

-- ex1: "nil nat" becomes "nil", the "nat" is the implicit argument that gets autofilled

-- ex2: "cons nat 4 (nil nat)" becomes "cons 4 nil", here we see {a: Type u} is "nat"

--

variables p : list nat

universe u

--implicit arguments are just notation shortcuts

constant consImplicit {a : Type u } : a -> list a -> list a

constant nilImplicit : Π {a : Type u}, list a

#check consImplicit --?M_1 → list ?M_1 → list ?M_1

--consA shows metavar like ?M_1

--using @ fills in the metavar with types

#check @consImplicit

#check nilImplicit

#check consImplicit 4 nilImplicit

--explicit arguments

constant consExplicit (a : Type u) : a -> list a -> list a

constant nilExplicit : Π (a : Type u), list a

#check consExplicit

#check consExplicit

#check consExplicit 4 nilExplicit --error

#check consExplicit 4 nilExplicit --error

#check consExplicit nat 4 (nilExplicit nat) --ok7.2 Pi-type, forall, parenthesis

-- notice that we Pi-type == forall or we can push the quantifier into a parenthesis.

-- three cons below are the same.

constant consA : Πa : Type u , a -> list a -> list a

constant consB : ∀a : Type u , a -> list a -> list a

constant consC : ∀(a : Type u), a -> list a -> list a

constant consD : Π(a : Type u) , a -> list a -> list a

constant consE (a : Type u) : a -> list a -> list a8 Simple interpreter

section basiclang

inductive Term : Type

| T : Term

| F : Term

| O : Term

| IfThenElse : Term -> Term -> Term -> Term

| S : Term -> Term

| P : Term -> Term

| IsZero : Term -> Term

open Term

def eval : Term -> Term

| (IfThenElse T s2 s3) := s2

| (IfThenElse F s2 s3) := s3

| (IfThenElse s1 s2 s3) :=

let ns1 := eval s1 in (IfThenElse ns1 s1 s2)

| (S s1) :=

let ns1 := eval s1 in (S ns1)

| (P O) := O

| (P (S k)) := k

| (P s1) :=

let ns1 := eval s1 in (P ns1)

| (IsZero O) := T

| (IsZero (S k)) := F

| (IsZero s1) :=

let ns1 := eval s1 in (IsZero ns1)

| _ := F

#reduce eval $ P $ S $ P O

#reduce eval $ IsZero O

#reduce eval $ IfThenElse (IsZero O) (S O) (S $ S O)

--- s1 -> ns1

--- ---------------

--- S s1 -> S ns1

def ToNat : Term -> nat

| O := 0

| (S (n: Term)) := 1 + ToNat n

| _ := 1

#reduce ToNat (eval $ S $ S $ S $ O)

end basiclang

--extensionality vs intensionality

--extensionality means functions that behave the same are the same

--intensionality means functions that behave the same but built differently are not the same

def foo : ℕ → ℕ → ℕ

| 0 n := 0

| (m+1) 0 := 1

| (m+1) (n+1) := 2

#reduce foo 5 0

section Combinators

def I {a : Type*} : a -> a := λx , x

def K {a b: Type*} : a -> b -> a := λx , λy, x

def app {a b: Type*} : (a -> b) -> a -> b := λf, λx, f x

def S {a b c: Type*} : (a -> b -> c) -> (a -> b) -> a -> c := λf, λg, λa , f a (g a)

#eval I 2

#check S K S K

#check K K (S K)

#check (S I I)

end Combinators

#reduce (λx, x + 2)59 Understanding Coq

What below means is that pairn :: nat -> nat -> natprod aka pairn (n1 n2) :: natprod

(* correct version *)

Inductive natprod : Type :=

| pairn (n1 n2 : nat).What below means is that pairn :: Π(na : nat) -> Πi(nb : nat) -> nat -> nat -> natprod na nb

Inductive natprod (na nb : nat): Type :=

| pairn (n1 n2 : nat).- Inductive is not Definition

Inductive bleh (one : Type a) : Type := ...

Definition bleh (one: Type a) : Type := ...